The Struggle of Old Filament

If you make a purchase using a shopping link on our site, we may earn a commission. Learn More

One of the biggest changes I’ve seen in 3D printing since I started is in the filament we use. Which is a good thing, because filament in the earlier days was terrible.

Although we have lots of different filament types to choose from now, PLA and ABS used to be the most common choices by far, with PETG as a distant third. From what I remember, those three materials were the vast majority of what you’d find for sale online or in stores. And all three were notably different back then than they are today.

PLA was still the most popular choice for standard 3D printing, largely due to its lesser heating requirements. A lot of older printers couldn’t heat the hotend past 225 degrees C, and would struggle to heat the bed to the temperatures required for other materials. Some printers didn’t have a heated bed at all, so PLA would have been the only real option for those machines.

But PLA back then was worse than what we have today. It had a waxy consistency when printed, and was more brittle than modern PLA. If it wasn’t printed at the right temperature, it would tend to break along layer lines easily. And that type of failure was more common than it is now, because it seemed more sensitive to printing temperature than modern materials. Finally, it was mostly only available in semi-translucent colors, which made it less attractive than other options.

What we know today as PLA was introduced at some point as a more premium filament under varying marketing terms like “premium PLA” or “PLA+”. I haven’t done the research on what actually changed on a material level, but there must have been some type of modification to the formula of the plastic because the premium variants were notably better in color and consistency. This eventually became the new standard PLA, although you will sometimes still see manufacturers advertise their filament as being PLA+.

Because of these shortcomings, people would sometimes turn to ABS for its greater strength and the fact that it was the only type of filament you could get in an opaque matte color. Old ABS had all of the same printing challenges of modern ABS, such as the higher printing temperature requirements and an infuriating tendency to warp. In some cases the warping was a more prevalent issue, but I think that was some combination of older 3D printers having a hard time heating the bed to 100C and most of us not having figured out that an enclosure really, really helps for ABS.

But ABS had another problem that I haven’t seen on any filament in years now, which is that it tended to burn easily. If you left the hotend heated up for a few minutes with ABS filament loaded, such as while fighting with your 2013-era slicer software, the filament would actually burn in the hotend, and you’d have to remember to manually extrude some filament before printing to flush out the weird discolored filament.

This would also happen sometimes during normal printing, and the burned filament could easily jam up the hotend or nozzle. This was a bigger issue in the days when nozzles weren’t sold in ten-packs on Amazon with next-day shipping. I occasionally have flashbacks to a particular incident where I found myself carefully soaking a nozzle in acetone to try to dissolve the plug of ABS, since I’d read that acetone dissolved ABS. (It didn’t work at all, and definitely wasn’t worth inhaling acetone fumes for however long I tried that for.)

I rarely used PETG in my early era of 3D printing, but I remember it being a very stringy material that was always a pain to post-process. It also had some of the burning problems of ABS, although to a lesser degree. The other thing I remember about PETG is that it would wear down nozzles notably faster than other materials. That is probably still technically an issue today, but with more printers using hardened steel nozzles, it’s not as much of a concern.

Whichever of these great options you chose to use with your 3D printer in 2013, the other problem you might have encountered is actually buying the filament. As you might imagine, filament wasn’t quite as easy to find back when 3D printing was a more obscure hobby. I do believe Amazon sold filament, but its pricing wasn’t any better than other sources, so many people shopped at other sites or physical stores. And you often had to go to a filament supplier if you wanted an “exotic” material such as PETG.

The filament was more expensive, too. I think I recall a 1kg spool of standard PLA costing at least $25, and ABS was more expensive than that. Those prices aren’t outlandish now for specialty colors or materials, but it made experimentation and functional prints a lot more expensive than they are now.

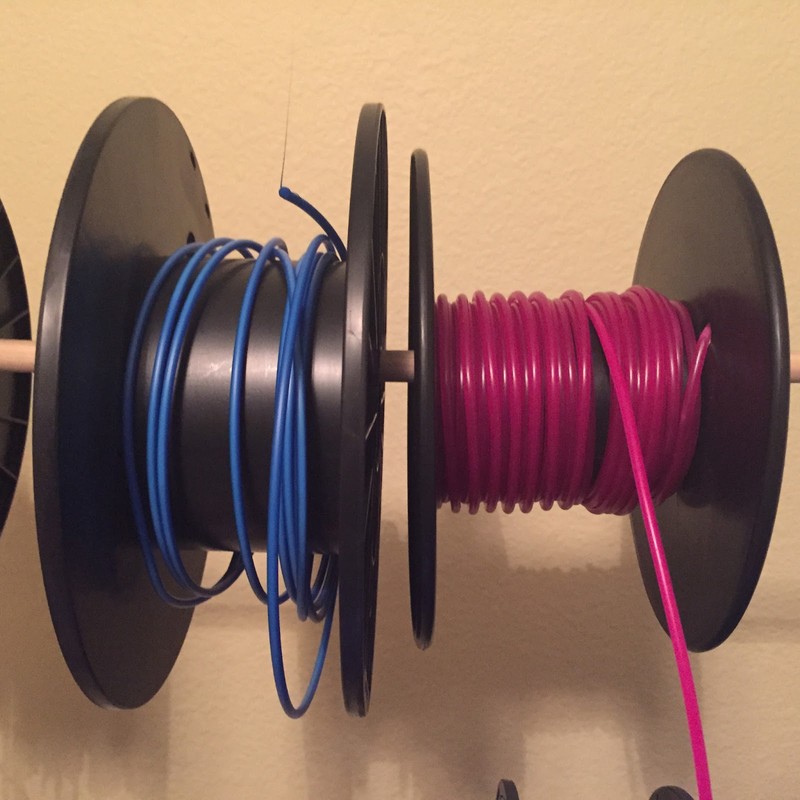

Finally, you had to make sure to get the right kind of filament, because there used to be two sizes—1.75mm and 3mm diameter. Almost every 3D printer today uses the 1.75mm variety, and it’s not surprising that the smaller size won out. It’s more flexible and breaks less easily than the 3mm size. But the two sizes used to be much more evenly distributed, and my first printer used the 3mm size. I’m certainly happy we don’t have to pay too much attention when shopping these days, although sometimes I do still see “2.85mm” filament for sale, so it’s still worth taking a moment to verify. That’s the problem with competing standards, it always takes way too long for the loser to fully die.

Overall, filament has come a long way since the early days of 3D printing, and I sometimes forget to appreciate just how much better filament is now. What’s interesting to me is that most of the improvements in modern filament came with relatively little fanfare or visibility. It just silently got better and now we all get to benefit from it.

However, there is at least one thing that has remained the same in filament from 2013 to now: some PLA still smells like waffles. Why? I have no idea.

Read more from the History of 3D Printing series

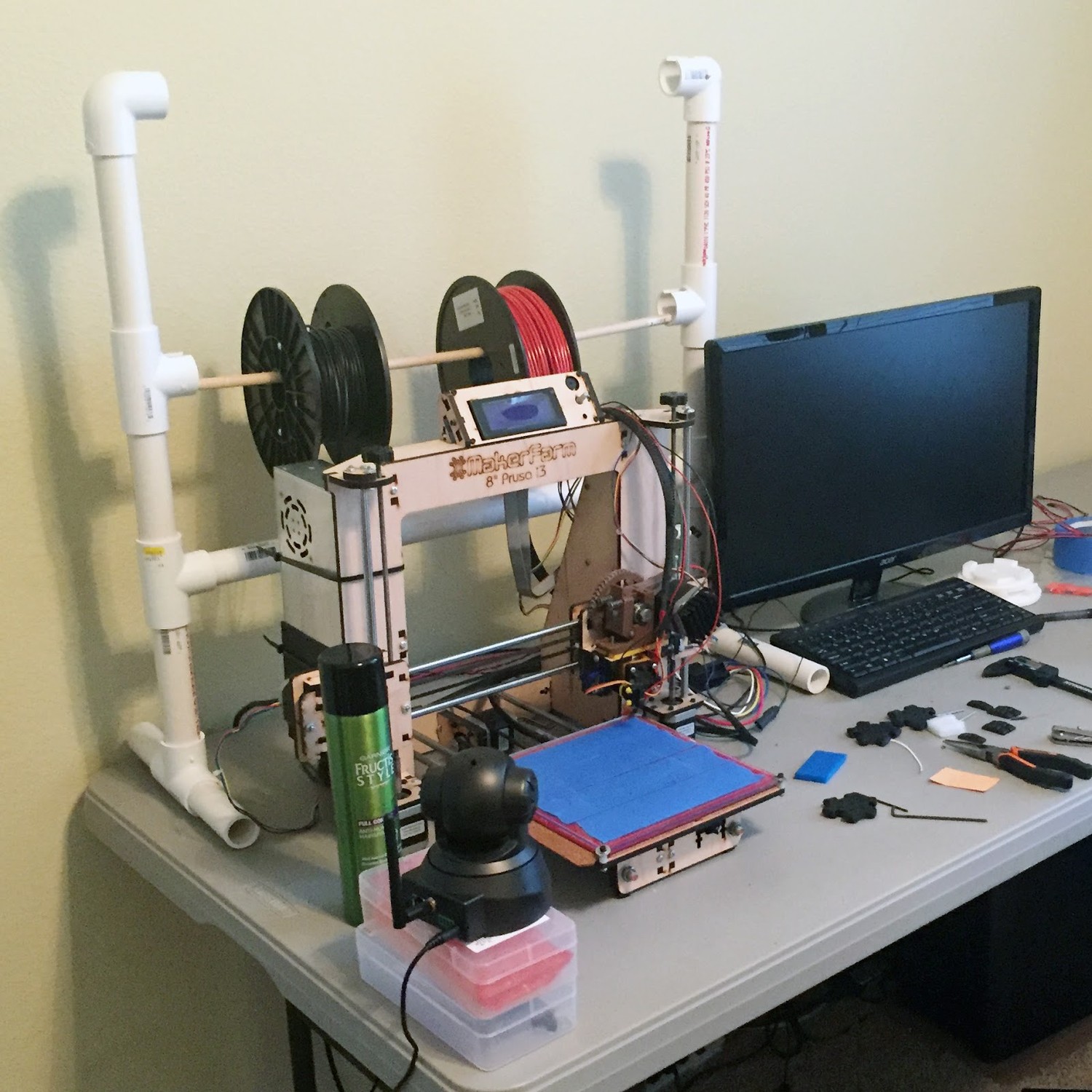

Origin Story: My Wooden 3D Printer

May 27, 2024

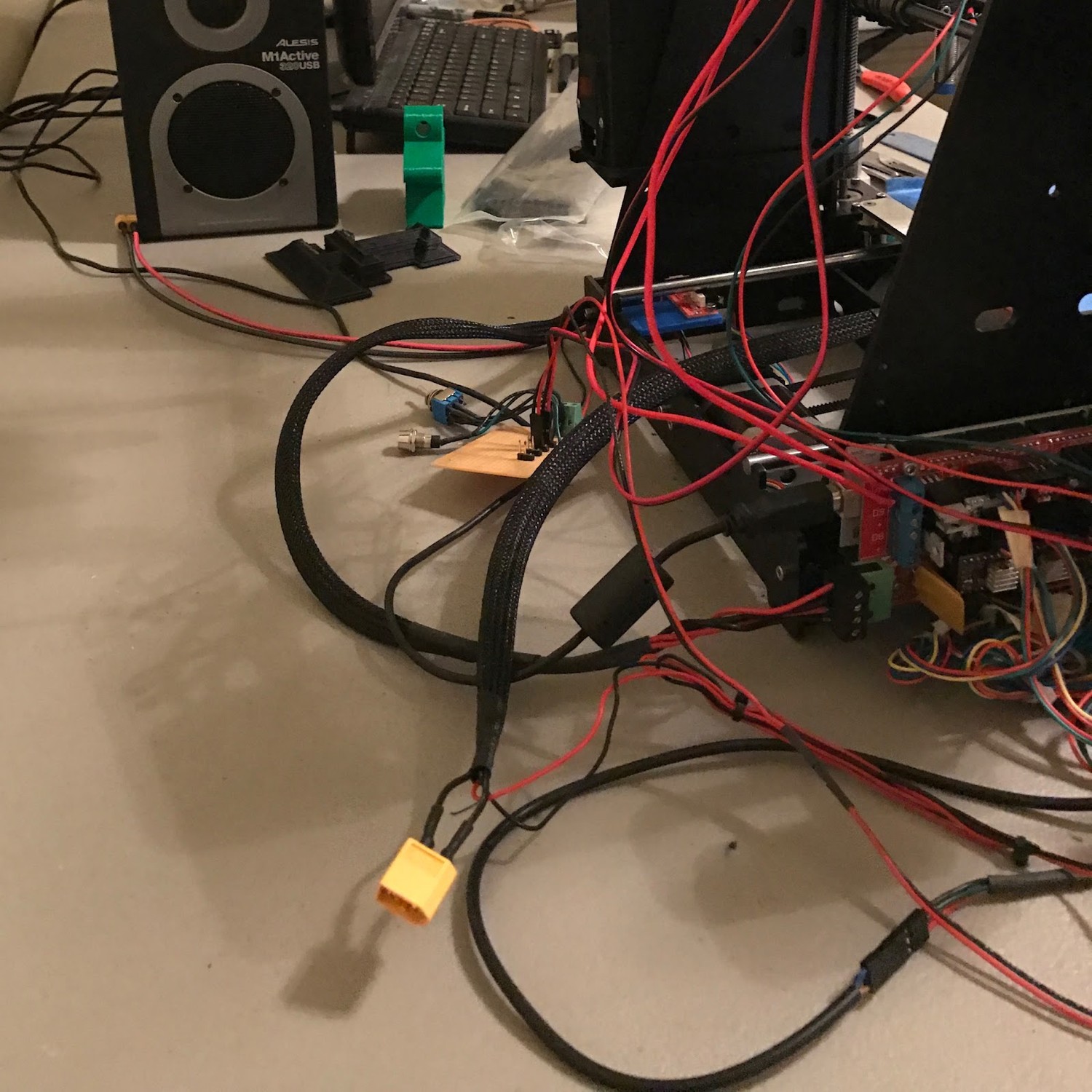

The Electronics of Early 3D Printers

June 5, 2024